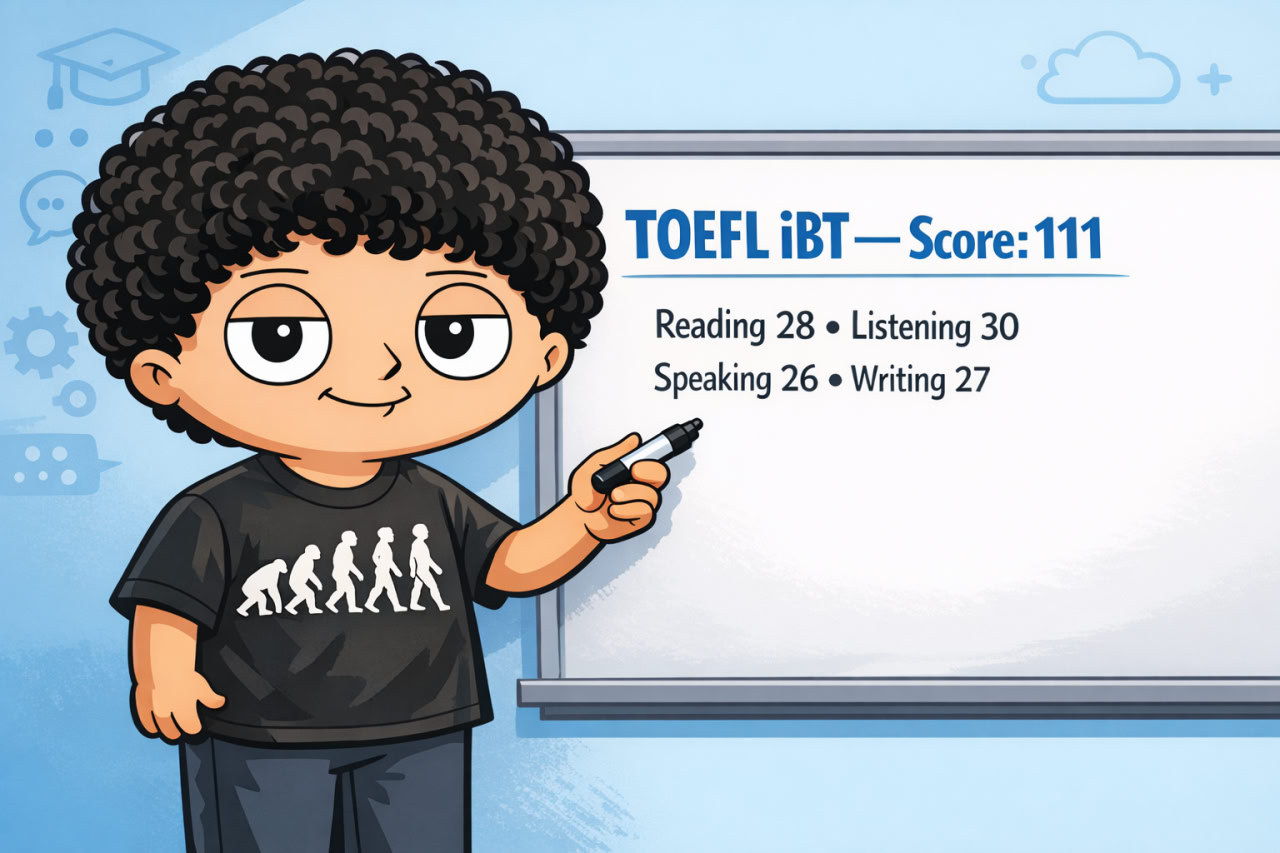

How I Scored 111/120 on the TOEFL iBT

After scoring 111/120 on the TOEFL iBT (Reading 28, Listening 30, Speaking 26, Writing 27), I'm sharing the exact strategies, templates, and mindset shifts that helped me get there. This isn't about improving your English overnight—it's about extracting maximum value from your current level.

On January 3rd, 2026, I took the TOEFL iBT and scored 111 out of 120:

| Section | 📘 Reading | 🎧 Listening | 🗣️ Speaking | ✍️ Writing | 🏆 Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Score | 28 / 30 | 30 / 30 | 26 / 30 | 27 / 30 | 111 / 120 |

I want to share the strategies that worked for me—not because my approach is the only way, but because I learned some counterintuitive lessons that might help others in similar situations.

First: Know What Score You Need and Why

Before diving into preparation, figure out what score you actually need. Are you applying to a university with a minimum of 100? Do you need a visa that only requires 79? Your target score should shape your entire preparation strategy—there's no point grinding for a 115 if 90 opens the door you need.

Here's the official TOEFL iBT to CEFR equivalency from ETS, alongside the IELTS-to-TOEFL concordance:

| CEFR Level | TOEFL iBT (0–120) |

|---|---|

| C2 | 114–120 |

| C1 | 95–113 |

| B2 | 72–94 |

| B1 | 42–71 |

| IELTS | TOEFL iBT |

|---|---|

| 9.0 | 120 |

| 8.5 | 115–119 |

| 8.0 | 108–114 |

| 7.5 | 100–107 |

| 7.0 | 91–99 |

| 6.5 | 81–90 |

Most universities require B2–C1 range (TOEFL 72–100+), while visa requirements tend to be lower.

Also, consider why you're choosing TOEFL over alternatives like IELTS. In my view, TOEFL tends to be a better reflection of actual English proficiency. ETS updates the TOEFL format regularly (the most recent change was in 2026) to keep up with how language competency is best measured. IELTS, by contrast, has remained largely unchanged for many years, which means its format is more predictable. That's not to say IELTS is easier—both tests require strong English skills—but TOEFL's evolving format tends to emphasize authentic academic communication more directly.

The Mindset Shift: You're Not Here to Learn English

Here's the uncomfortable truth I had to accept early on: you cannot significantly improve your English proficiency in a few weeks of TOEFL preparation. English fluency is built over years of consistent exposure and practice.

What you can do is learn to demonstrate your ability effectively under test conditions.

The TOEFL isn't testing whether you're a native speaker. It's testing whether you can demonstrate academic English competency within very specific formats. Once I stopped thinking "I need to improve my English" and started thinking "I need to communicate effectively in academic formats," everything changed.

A crucial clarification: The techniques I describe in this guide—templates, note-taking structures, active reading—are not hacks or tricks to game the system. They're fundamental academic skills you should be using in real life anyway. If you're in a university lecture, you should be taking structured notes. If you're reading academic papers, you should be reading with purpose. These strategies don't compensate for lack of ability; they help you demonstrate the ability you already have under timed conditions. There are no magic shortcuts here—just practical patterns for effective communication and comprehension.

Strategy #1: Take a Diagnostic Mock Immediately

Before starting any real preparation, but after learning the basics about the test format, I took a full mock test. This was uncomfortable—I made timing mistakes, and my score was lower than I wanted.

But this "fresh" mock gave me something invaluable: a baseline understanding of where I actually stood, not where I thought I stood.

Many people spend weeks consuming preparation content before attempting a real practice test. This is backwards. You need to experience the test first to understand:

- Which sections are genuinely difficult for you vs. which just need format familiarity

- How time pressure actually affects your performance

- What your realistic target score range looks like

Take your diagnostic mock immediately after understanding the basic test structure—not after you feel "ready."

Strategy #2: Structure Your Communication

The key was realizing that the structure should be automatic so your brain can focus entirely on content. I developed specific templates for each section—not as hacks or tricks, but as frameworks for clear academic communication:

Speaking

The Speaking section terrified me initially. Forty-five to sixty seconds of uninterrupted talking with no time to think?

Task 1 (Independent):

I personally believe [position] for a couple of reasons.

To begin with, [reason 1]. For instance, [example].

On top of that, [reason 2]. To illustrate, [example].

Task 2 (Integrated Campus):

The [announcement/letter] states that the university [is going to/should] [describe the change or proposal].

This is because [give reason(s) from the reading].

The [man/woman] in the conversation [agrees/disagrees] with this change.

First, [he/she] points out that [reason 1]. [He/She] explains that [detail].

Second, [he/she] mentions that [reason 2]. According to [him/her], [detail].

Task 3 (Integrated Academic):

The reading introduces [term], which is [definition].

The professor illustrates this by giving [one example / two examples].

First, [he/she] talks about [example 1]. [He/She] explains that [how it shows the concept].

Second, [he/she] gives the example of [example 2]. [He/She] points out that [how it shows the concept].

Task 4 (Lecture Summary):

The professor explains [topic] and describes [one way / two ways / two types / two examples] of how this works.

First, [he/she] discusses [first point/type/method]. [He/She] explains that [details 1]. For example, [example 1].

Second, [he/she] discusses [second point/type/method]. According to the professor, [details 2]. [He/She] gives the example of [example 2].

Writing

Integrated Writing:

The article introduces the topic of ____

The writer says ____

The lecturer disagrees because he/she believes ____

First, the author says ____

The reading passage states ____

The professor believes there are flaws in the author's position.

He/She contends ____

He/She goes on to say ____

Second, the reading passage claims that ____

The speaker, on the other hand, points out ____

He/She argues that ____

Finally, the reading passage notes ____

The professor rebuts this argument. He/She says ____

In fact, he claims ____

Academic Discussion:

I agree with [NAME] that [THEIR POINT], and I would add that [YOUR OPINION].

This is important because [REASON]. For instance, [EXAMPLE].

While [NAME] raised a relevant point about [THEIR POINT], this approach may overlook the fact that [WEAKNESS].

Key elements to focus on:

- Agreeing with a classmate's point and building on it with your own opinion

- Supporting your position with a clear reason and a concrete example

- Acknowledging another classmate's view while pointing out its limitation

These templates became so automatic that during the actual test, I never had to think about structure—only content.

Strategy #3: Note-Taking Tables for Integrated Tasks

Templates tell you what to say, but you also need a system for what to write down during the reading and listening portions.

I created simple tables that I'd recreate on scratch paper:

For Speaking Task 2:

| READING | Notes |

|---|---|

| Stance | |

| Reason 1 | |

| Example 1 | |

| Reason 2 | |

| Example 2 |

For Speaking Task 2:

| READING | Notes |

|---|---|

| Topic/Change | |

| Reason 1 | |

| Reason 2 |

| LISTENING | Notes |

|---|---|

| Opinion | Agree / Disagree |

| Reason 1 + Detail | |

| Reason 2 + Detail |

For Speaking Task 3:

| READING | Notes |

|---|---|

| Term/Concept | |

| Definition |

| LISTENING | Notes |

|---|---|

| Example 1 + Details | |

| Example 2 + Details |

For Integrated Writing:

| Section | Reading Passage (Article/Writer) | Listening Passage (Lecture/Professor) |

|---|---|---|

| Main Topic | ||

| Point 1 | ||

| Point 2 | ||

| Point 3 | ||

| Overall Position |

These tables forced me to listen for specific information rather than trying to write down everything. During the response, I'd simply move through the table from top to bottom.

A practical tip: you can draw these tables in between sections while the instructions are playing, or even just sketch the table lines without writing the headers (like "Example", "Term/Concept", etc.)—just the empty structure. If you train enough with these templates, you'll internalize their structure and be able to set them up in seconds.

Another thing that helped me was writing down small reference notes on my scratch paper before the test started:

Gender pairs: For every listening task (Speaking 2, 3, 4 and Integrated Writing), I'd quickly note he/she or man/woman (and letter/announcement for Speaking Task 2) as soon as I heard the speakers. This prevented me from mixing up genders mid-response—a surprisingly easy mistake under time pressure.

Reporting verbs cheat sheet: I kept a small table of varied reporting verbs so I wouldn't fall back on the same few words I was used to:

| Descriptive | Argumentative |

|---|---|

| agrees | rebuts |

| states | refutes |

| mentions | disagrees |

| notes | argues that |

| points out | challenges |

| emphasizes | counters |

| explains | disputes |

This made my responses sound more natural and less repetitive, which matters for both the Speaking and Writing scores.

Strategy #4: Use AI as Your Personal Tutor

This is where Claude became invaluable. I used it to:

- Generate and review practice responses: I'd transcribe my spoken answers and get detailed feedback on content, grammar, and coherence

- Create 5/5 revision examples: For every response I practiced, I'd ask for a minimally-revised version that would score perfectly, with changes highlighted

- Identify patterns in my mistakes: Over multiple sessions, Claude helped me notice recurring errors (like subject-verb agreement issues or article usage)

- Explain grammar rules in context: Instead of studying grammar abstractly, I learned rules through my actual mistakes

- Suggest better vocabulary: For places where I used simple or repetitive words, Claude would suggest more advanced alternatives that fit the context naturally

Here's an example of the prompt I used for the Integrated Writing task:

Please review the following TOEFL Integrated Writing task.

I will provide:

1. The reading passage

2. The lecture transcript

3. My response

Task:

- Analyze my response step by step, comparing it with both the reading and the lecture.

- Evaluate it according to TOEFL iBT Integrated Writing scoring criteria (2025 standards).

- Provide detailed feedback for each scoring category (e.g., content accuracy, integration of sources, organization, language use).

- Give an overall score and briefly explain the reasoning behind it.

- Identify specific weaknesses that prevent a perfect score.

- Produce a revised **5/5-scoring response** with the **fewest possible changes** from the original.

- **Highlight all changes in bold** so I can easily see what was modified.

- Suggest better vocabulary for places where I used simple or repetitive words.

Reading:

[paste reading passage]

Lecture transcript:

[paste lecture transcript]

My response:

[paste your response]

And here's the one I used for the Academic Discussion task:

Please review the following TOEFL Academic Discussion task.

I will provide:

1. The professor's question

2. The classmates' responses

3. My response

Task:

- Analyze my response step by step, considering how well it addresses the professor's question and engages with classmates' views.

- Evaluate it according to TOEFL iBT Academic Discussion scoring criteria (2025 standards).

- Provide detailed feedback for each scoring category (e.g., relevance, development of ideas, coherence, language use).

- Give an overall score and briefly explain the reasoning behind it.

- Identify specific weaknesses that prevent a perfect score.

- Produce a revised **5/5-scoring response** with the **fewest possible changes** from the original.

- **Highlight all changes in bold** so I can easily see what was modified.

- Suggest better vocabulary for places where I used simple or repetitive words.

Professor's question:

[paste the professor's question]

Classmates' responses:

[paste classmates' responses]

My response:

[paste your response]

The key was treating each practice session as a feedback loop, not just repetition.

Strategy #5: Practice with a Partner

I practiced speaking tasks with a partner, and we'd review each other's transcribed responses. This helped in two ways:

- Hearing different approaches to the same prompt expanded my mental library of examples and phrasings

- Explaining someone else's mistakes solidified my own understanding of what good responses look like

Even if you can't find a study partner, consider recording yourself and reviewing your responses as if they were someone else's.

Strategy #6: Start Earlier Than You Think You Need To

I cannot stress this enough: preparation time compounds. The strategies I've described—building templates, creating note-taking systems, practicing with feedback—take time to become automatic.

If you start two weeks before your test, you'll spend the whole time learning these systems. If you start six weeks before, you'll have four weeks to actually practice using them until they're second nature.

The test date feels far away until it isn't. Book your test, then work backwards from that date to create your preparation schedule.

Strategy #7: Mock Tests Are Non-Negotiable

I took 5 full mock tests over about 1.5 months of preparation. Not partial sections, not untimed practice—full, timed simulations.

Each mock test taught me something:

- How my energy levels change across a 2+ hour test

- Which sections I tend to rush and which I have extra time

- How my performance degrades when I'm tired

- What my actual score range looks like (not my optimistic estimate)

Free resources like ETS's official practice tests are gold. Use them.

What I'd Do Differently

Looking back, I wish I had:

- Started my focused preparation even earlier

- Done more speaking practice with real-time recording

- Spent less time on passive content consumption and more on active practice

Reading

Skip the Pre-Reading

Unlike some test-takers who read the entire passage (or at least the first and last sentence of each paragraph) before answering questions, I took a different approach: I started answering Question 1 immediately, reading only what I needed for each question.

Here's why this worked:

- Active reading vs. passive reading: Pre-reading the passage is passive—you're reading without a clear purpose. Question-driven reading is active—you're reading to answer a specific question. This focus makes comprehension stronger and retention better.

- No information loss: By the time you finish reading a full passage and start answering questions, you've already forgotten key details. Reading on-demand keeps everything fresh.

- Massive time savings: This approach gave me so much extra time that I could review uncertain answers multiple times. This is why I scored 28—I had time to fix mistakes.

- Some questions don't need the passage: Vocabulary questions, for instance, are usually about the word itself, not some special contextual meaning. You can answer them directly.

Sentence Insertion Strategy

For sentence insertion questions, I'd:

- Read the sentence first

- Try placing it mentally in each spot

- Look for connection words (this, these, however, therefore) and see what they refer to

- Match logical flow

These reference words and transitions were my biggest clues for finding the right position.

No Note-Taking

I didn't take any notes during Reading. Writing things down consumes time without meaningful benefit—the passage is always there to re-read if needed.

Listening

Structured Notes, Not Transcripts

I scored 30/30 on Listening, and my note-taking strategy was key: write selectively, not everything.

Many test-takers try to transcribe what they hear. This is a mistake—you'll miss information while writing, and you'll end up with messy, unusable notes.

I took notes for two reasons:

- Concentration: Writing kept me actively engaged with the audio

- Key details: Some information (names, dates, examples) needs to be captured

Basic Note Structure

I used simple two-column layouts to organize information. For example for conversations between a professor and a student, I used this:

| Prof | Stu |

|---|---|

| ... | |

| ... |

This separation kept speakers' ideas distinct and made it easy to locate information during questions.

The key: listen first, write second. Capture main ideas and specific examples, not complete sentences.

Conclusion

A 111 score isn't perfect, but it opened the doors I needed it to open. More importantly, the process taught me that standardized tests are structured assessments with clear expectations—and once you understand what they're looking for, you can communicate more effectively.

Structured tests like TOEFL don't measure how "good" your English is in some abstract sense. They measure how well you can demonstrate specific competencies in specific formats under time pressure. Focus on that, and you'll show your true English level more accurately.

Good luck with your preparation.

Have questions about TOEFL preparation? Feel free to reach out.